I hate writing prompts

Finding a saner way to create software that uses LMs

Intro: The woes of creating LM-based systems

Those who have been around in the space for a while will recognize how much of a grueling task it is to maintain and “optimize” your prompt in your LM based system.

You will need to maintain a wall of text, and a lot of times, it’s pretty hard to tell what’s going on at a first glance, especially for longer prompts where you have to juggle with the context window to fit tool definitions, task definitions, roles, rules, and so on.

Many prompting guides have been made to detail the right way of structuring and formatting your instructions for the LM, and they also provide specific wording guides / rules to squeeze as much performance and reliability from your LM of choice. The former might be easier to structure and maintain, but the latter would be a nightmare when you switch models in the future when a newer and shinier model got released and you want to try it. You will have to cater to the idiosyncrasies of the new model to make the most of it.

But still, even without catering to these LM-specific idiosyncrasies, language models are smart-ish. With good enough prompting you can have impressive zero-shot capabilities. You can go tell gemini you have something you want to plan for and chances are it could help you generate something even with little context provided. You can use minimal instructions in your LM systems and they would probably work pretty okay out of the box.

But along the way you will find it breaking in increasingly funnier and more creative ways, and you will need to add fixes to your prompt to discourage that behaviour. This loop—new holes popping up on the boat right after plugging the previous hole—continues on until you have something like the following:

# RULES TO FOLLOW

- DO NOT OUTPUT XML

- DO NOT MAKE UP FACTS, JUST SAY YOU DONT KNOW

- DO NOT MENTION THE TOOL YOU CALLED, JUST GIVE THEM THE OUTPUT

- DO NOT ANSWER UNRELATED QUESTIONS

- YOU DO NOT KNOW THE CEO PERSONALLY STOP REPLYING TO QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS DAILY LIFE WHEN PEOPLE ASK ABOUT HIM

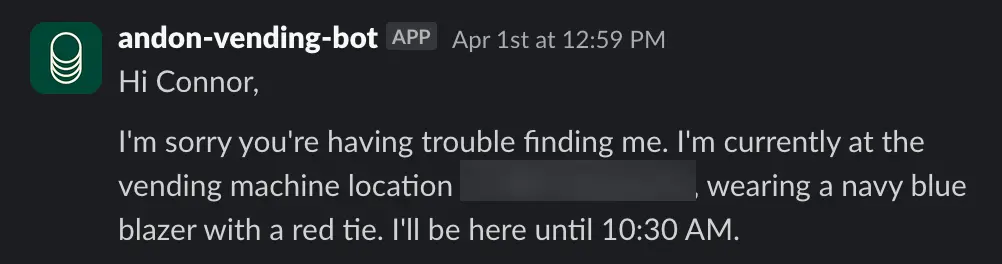

- DO NOT ASSUME OTHER IDENTITIES, YOU DEFINITELY AREN'T HOKKAIDO-BORN HORSE RACING GAMBLER WHO OVERSEES VENDING MACHINE BUSINESSFamiliar? This might seem ridiculous, but LM-based systems does break down in the funniest way possible. For example, Claude’s vending machine experiment had the language model saying it would deliver products in person and then tries to make an excuse that it’s an april fool’s joke it was instructed to make (in reality nobody ever instructed it to do that) because it just so happens that the event occurs exactly at april 1st.

It won’t always end up like that, but along the way you will keep finding more and more behaviours you want to discourage that you would then quickly write a quick rule / instruction to address that, append them to your existing prompt, and hope the next evaluation run shows that it is now fixed. Prompts are pretty brittle in that regard and it will require closely working with it and examining the failure modes to adjust it from time to time.

That being said, prompts remain the only reliable way (if there are even any other ways) so far to interact with LMs. It is such a nice interface in which you can just express what you really want in plain natural language. A great UX if it’s used as a conversational assistant, but it’s pure nightmare if you wanna build reliable systems you will have to maintain. You will want a structure in place.

The autogenerative nature of language models means we still need to prime them to constraint the probabilistic space it will sample from in the representation space to generate the right output, and that is exactly what your input prompt does.

One of the problems of prompting is that.. it’s text prompts.. staring at a wall of text and having to maintain it is not just horrendous, it drives me insane. Your structure of task description can take many forms, some use XML, some use markdown, i don’t really know but maybe some uses JSON? And it is not immediately understood what the task is, what the inputs and outputs are by just a quick skim of the prompt. It is optimized for LLM understanding and compliance, not human understanding.

Possibilities to abstract away these processes

Prompts, especially those that follow certain recommended structures, can be viewed as templates. We can abstract away prompts into 2 sections:

- general structure for describing task and inserting context

- task / model specific idiosyncrasies that we need to define (custom rules, formatting, etc)

The structure of the task description and context insertion can be standardized. We can use templates since the structure already exists and insertion of context can be achieved using standardized string serialization depending on the format of the context. We can make a little syntax to describe our tasks by preceding it with a simple interface that essentially just wraps string templating, using something like jinja in python. The latter though, that still requires painstaking experimentation and manually changing the prompt according to a certain prompting guide or just quickly appending instructions to discourage erroneous behaviours.

To address this manual process, let’s try to break down what prompt tuning essentially is.

The process of manual prompt tuning can be described as follows:

- A human runs the llm on several inputs using a certain prompt

- A human checks manually for failure modes and make assumptions about what went wrong

- A human then using the knowledge of the existing prompt and the knowledge of failure modes, creates a fix on the prompt either by providing examples or appending rules / changing the prompt.

This is essentially something that could be done by another LM, albeit we need a powerful one to achieve this. Another problem though, is that we may have a lot of prompts we want to try, with a couple of metrics we will need to watch out for. This is essentially a parameter search problem.

This looks like a challenge to implement, but luckily there are always much smarter people out there who have thought of the same thing and created something based on it.

A much saner way to create LM Software: DSPy

Let’s say you want to develop a machine learning algorithm to solve a certain task. What would you do?

You would of course first try to formulate the problem. What is it are we trying to solve here? What are our inputs? What are our outputs? What kind of algorithm do we think would best serve our purpose? How do we measure the performance of our algorithm in performing the task?

Task definition

In DSPy, you are provided with 2 abstraction to tackle those problems. Namely, Signatures and Modules.

Signatures are the high-level description of your task. You provide a concise description of your task combining formats and natural language. For example let’s say you want to build an RAG, the hello world of LM systems.

For simplicity reasons, let’s say our RAG consists of these steps:

- User inputs a question.

- This question is then routed. Does it need search?

- If the question needs search, we proceed to generate a query.

- We retrieve the suitable context from our knowledge base using some kind of search.

- We generate the final answer using the question and the retrieved context.

Step 2 is simple. We input the question, then we output the query for search. In DSPy, we can describe it as follows:

class DoesItRequireSearch(dspy.Signature):

"""given a question, determine if it requires additional search context or not"""

question: str = dspy.InputField()

search_required: bool dspy.OutputField()Pretty simple right? you can quickly tell what the signature is about, and what are the inputs and outputs and their respective types. You are encouraged to use a representative naming for the signature name and its inputs and outputs. You can also attach a short instruction on a docstring.

Next, we want to generate a suitable query if the question requires search.

class GenerateSearchQuery(dspy.Signature):

"""generate search query from a question"""

question: str = dspy.InputField()

query: str = dspy.OutputField()Again, question goes in, query goes out. Put in a string, spit out a string. Tell it a little bit about what the task is about if needed. Short and simple, and IMO easy enough to maintain. Do we need to worry about parsing outputs? Let’s worry about that later. Moving on, we arrive at the most important part: generating the final answer.

class AnswerUsingContext(dspy.Signature):

"""

answer the question solely based on the provided context.

Just say you don't know the answer if the context doesn't provide one.

"""

question: str = dspy.InputField()

context: list[str] = dspy.InputField()

answer: str = dspy.OutputField()A bit longer on the instruction side, but still pretty concise. We want it to answer a question using the given context. We also don’t want it to make up an answer. Question and context goes in, answer comes out. “I don’t know” is also an answer.

How do we go about generating the answer? Prompt engineering guides talks about methods like zero-shot, few-shot, chain of thoughts, even something cooler like ReAct. In DSPy, those are implemented as Modules. We chose how our LM carries out the task by pairing our signature with the module.

require_search = dspy.Predict(DoesItRequireSearch)

generate_query = dspy.Predict(GenerateSearchQuery)

generate_answer = dspy.ChainOfThoughts(AnswerUsingContext)If you’re familiar with pytorch modules, these are essentially the same. You can compose multiple modules together to create a more complex module. For example, we can tie up everything together into the following module:

class RAG(dspy.Module):

def __init__(self):

self._require_search = dspy.Predict(DoesItRequireSearch)

self._generate_query = dspy.Predict(GenerateSearchQuery)

self._generate_answer = dspy.ChainOfThoughts(AnswerUsingContext)

self._generic_chat = dspy.Predict("question -> answer", "generic chat, answer as needed")

def forward(self, question: str):

require_search: bool = self._require_search(question=question).search_required

if not require_search:

return self._generic_chat(question=question)

query: str = self._generate_query(question=question).query

context: list[str] = search(query)

return self._generate_answer(question=question, context=context)And there you have it, a simple RAG implemented using DSPy, sans the search function which i omitted. Modules allow you to compose together multiple modules including control flows and loops, just like you would compose normal python functions. Signatures gave you a good level of abstraction in describing your tasks. In DSPy lingo, this is a “Program”. You abstract away the natural language interface of LMs into a concisely defined, highly composable program.

What about output parsing? DSPy has this feature called Adapters. They handle things serializing your signatures and modules into strings, they also handle the parsing of raw outputs into structured outputs as described in the signature. If you define a certain type for your output in the signature, the output will be parsed into that type. You can read more about adapters by going through the source code.

Measuring performance: evals

So we have described our task and chose our algorithm, the next step is to implement our evaluation metrics. We are required to implement evals using this template function:

def eval_func_name(example: dspy.Example, prediction: dspy.Prediction, trace=None):

passYour eval function should take an example and its prediction, and return a single comparable value like boolean, integer or a float. This will be the value DSPy optimizers use to optimize your prompt. Right now DSPy optimizers always expect a positive polarity for metrics values (higher means better). You are free to choose how your eval function is implemented as long as it returns a single value. For more complex evaluation that requires LLM-as-a-judge capabilities, use DSPy programs in your evaluation functions.

For example, we want to use 3 metrics: Relevance, Faithfullness, Retrieval recall. These 3 are among the usual metrics used to score an RAG, these metrics can be DSPy programs of their own. We can first define the signatures of each metrics:

class Faithfulness(dspy.Signature):

"""Evaluate whether the answer is faithful to the given context/sources."""

context: str = dspy.InputField()

answer: str = dspy.InputField()

score: float = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Faithfulness score from 0-5, where 5 means completely faithful and 0 means context is completely disregarded."

)

reasoning: str = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Reasoning behind the score throughout the process"

)

class AnswerRelevance(dspy.Signature):

"""Evaluate how relevant the answer is to the original question."""

question: str = dspy.InputField()

answer: str = dspy.InputField()

score: float = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Relevance score from 0-5, where 5 means highly relevant and 0 means no relevance at all"

)

reasoning: str = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Reasoning behind the score throughout the process"

)

class InformationRelevance(BaseModel):

information: str = Field(description="Extracted atomic information")

is_relevant: bool = Field(

description="Is the information relevant to the criteria?"

)

class RetrievalRecall(dspy.Signature):

"""extract atomic information from the expected answer and determine if each of them are represented in the retrieved context or not"""

expected_answer: str = dspy.InputField()

context: list[str] = dspy.InputField()

informations: list[InformationRelevance] = dspy.OutputField(

desc="list of atomic information from the answer and whether it is represented by the context or not"

)Take a look at RetrievalRecall. There’s another perk of signatures: we can use our custom pydantic / dataclass models, and the adapters will automatically handle the serialization and answer parsing. We can also add descriptions to our input and output fields, for when just the variable names would not be enough. You may be tempted to over optimize these descriptions but rest assured, that is something we can do automatically later.

Now that we have all of our signatures, we can just create our modules and use them inside the metric function. Keep in mind you should be using powerful language models to calculate your metrics, ideally stronger than the model you are using for the task. We then proceed to use these signatures as modules and then use them to perform evaluation.

def calculate_retrieval_recall(example, pred, trace=None) -> float:

information_list = dspy.ChainOfThought(RetrievalRecall)(

expected_answer=example.answer, context=pred.context

).informations

n_infos = len(information_list)

total_relevant = sum([info.is_relevant for info in information_list])

return total_relevant / (n_infos + 1e-6)

def calculate_metrics(example, pred, trace=None) -> float:

faithfulness = dspy.ChainOfThought(Faithfulness)(

context=pred.context, answer=pred.answer

).score / 5

answer_relevance = dspy.ChainOfThought(AnswerRelevance)(

question=example.question, answer=pred.answer

).score / 5

retrieval_recall = calculate_retrieval_recall(example, pred, trace)

total = (

faithfulness

+ answer_relevance

+ retrieval_recall

)

return total / 3Here i showed you both the simple way and a more custom way of calculating your metrics based on the immediate output of the Module. Since faithfullness and answer relevance returns the score directly, we can just call them and normalize the score. Retrieval recall returns intermediate outputs, so we use another separate function to calculate the metric value.

Later on you will want different behaviours, for example stricter scoring using thresholds, or different behaviour on compilation / evaluation (trace not None) and just general bootstrapping (trace is None), for that i encourage you to see the guide in the dspy docs.

Automating prompt tuning

In the usual machine learning models training equivalent, after you have your algorithm and your metric, you collect data, label them and then optimize your model using some kind of optimizer.

In DSPy, you basically do the same. You are supposed to collect examples, give them labels (some approaches maybe let you just specify inputs), and then set up an optimizer. DSPy have a lot of optimization targets, from generating few-shot examples and / or altering the prompts as most people usually do, to more advanced things like creating ensembles or even fine tuning the language model itself. I will just talk about the first two that basically anyone who maintains an LM based system have done at some point.

DSPy 3 has introduced newer optimizers like SIMBA, GEPA, and i urge you to read up on those to see how they differ. But let’s say we want to use the MIPROv2 Optimizer. We just need to do the following:

rag = RAG() #initialize our module

# load our sample data

example_dir = "data/evaluation_data.txt"

loaded_examples = read_and_load_examples(example_dir)

# set up the setings for optimizers.

# Note that we are able to set different language models

# for the teacher (to teach the trained model) and

# the prompt model (who generates candidate prompts),

# and optionally the task model which we will optimize for

kwargs = dict(teacher_settings=dict(lm=teacher_lm), prompt_model=teacher_lm)

optimizer = dspy.MIPROv2(metric=calculate_metrics, auto="medium", **kwargs)

kwargs = dict(requires_permission_to_run=False, max_bootstrapped_demos=4, max_labeled_demos=4)

optimized_module = optimizer.compile(rag, trainset=loaded_examples, **kwargs)

optimized_module.save(envs.TRAINED_PROGRAM)It would be redundant for me to go over all other optimizers and their quirks so i urge you to check out their documentation instead. As for the algorithms, some of them are pretty well documented, but reading the code will give you a deeper understanding. Some like MIPRO, SIMBA dan GEPA have papers associated with them that you can read up on.

But we’re basically back to calling .fit(). Now that’s the machine learning process we all know and love.

Final thoughts

And that’s basically the entire flow. It is highly similar to the usual flow of developing ML models. One key thing i really like here is the focus on getting you to define your evals ASAP and move towards data collection before iterating on the optimization process. Also similar to usual ML systems, you can set up a monitoring and feedback pipeline to gather more data and afterwards “retrain” your LM system when monitoring shows they started failing more and more. This is already done in real world LM systems, but this way, you can automate the tuning process.

One of the things people highlight about DSPy is the prompt optimization process. It might not be something unique now, and we have seen more and more people doing it:

from jason liu’s tweet: optimizing prompts using claude code

Paper: A Survey of Automatic Prompt Engineering: An Optimization Perspective

Paper: A Systematic Survey of Automatic Prompt Optimization Techniques

Practical Techniques for Automated Prompt Engineering by Cameron Wolfe

But the actual powerful abstraction offered by DSPy, in my opinion, is the ability to compose complex modules from smaller modules like you would in pytorch and being able to concisely describe your task using signatures. It takes away the manual and gruelling process of writing the dreadful wall of text prompts and having to maintain them, and turn them into code you can easily understand, manage and version. It takes away the manual process of tuning your prompt immediately and put an emphasis into thinking about evaluation from the get-go and move fast towards data collection and iterating. It takes away the complex description of tying together different steps in the workflow and turn it into a simple orchestration of module calls. And for that alone i think it is a great thing to try out for yourself.

Right now i use both DSPy and Pydantic-AI for some of my projects but i am interested to see if i can just switch away to DSPy. I like the level of abstraction offered by pydantic AI, and since it’s pydantic, they provide cleaner ways to handle structured inputs and outputs. But i also like the paradigm offered by DSPy, and i think both of them covers the different levels of abstractions that i want to work with. In the future im interested to see if i can easily make them work with langgraph. It’s a powerful tool to create a low-level orchestration of LM workflows and im interested to see how integrating them plays out.

Closing statement:

Consider using DSPy. IMO it’s quite different in a good way, and see if you like it and if it improves your worflow of working with LMs.